This will probably be the most incomplete, most unorganized Remembrance Day post I'll do for a good long while. While one I just felt was too large a story to tell in a night, the other is one which I quite literally don't have the entire story for. In the case of the former, I'm not sure I'll ever fully tell that story; of the latter, I can only say that one day I can hopefully put it onto pages and - if I can one day be good enough about it - to get it published and shown outside just theOtaku.com

This year I'm going to talk about "Operation Oblivion" and the men involved and how they branched out.

And for my final thoughts, I am going to tell you as much as I can of things my grandmother herself told me earlier in this week.

Operation Oblivion:

After three days, I'm sure you are all familiar that yes, in the 1930s and 1940s, Chinese-Canadians had it very rough and were not treated well by other white Canadians. They weren't allowed to become lawyers or pharmacists, couldn't vote - they weren't even really treated as Canadian citizens - and everyday life involved a racist norm.

When war erupted in the Pacific and in Europe, many Chinese debated what to do: would they go to war for their country, or would they abstain from a war in the name of a country that did not even want them? The Chinese Head Tax from 1885 had embittered many immigrants already, and the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act (which even coincided with Canada's birthday on July 1st) gouged the rift deeper. Despite all this, Chinese-Canadians still remained the highest ethnic minority to volunteer for enlistment in the country.

Once Canada understood the need for Chinese troops and agents - as well as understanding America's glad acceptance of any able-bodied Canadian volunteers and Britain's urging for Chinese operatives for the S.O.E. work in Asia - the wheels finally started to move. In 1944, better late than never, Canada began enlisting and training her Chinese citizens.

Enter "Operation Oblivion".

Operation Oblivion was so named for the simple fact that it was a suicide mission. The mission was to take thirteen Chinese-Canadian operatives - men who could speak with the locals and above all else look like the locals - and parachute them deep into Japanese-occupied China. From there, thy would act as force multipliers (much like the modern US Green Berets) raising an army of 300,000 local Chinese and using weapons captured from the German Afrika Corps. Thirteen men against an entire continent - and yet they found their volunteers.

The operatives arrived in a training camp in the interior of British Columbia aptly named "Oblivion Camp". For months they trained in small arms, demolitions, unarmed combat and silent kill, wireless operation, boat operation, survival techniques, photography, propaganda, and among many others, ambush planning and execution.

Come September of 1944, the team went to Australia where they trained in parachute jumping and swimming while waiting for their orders and their transportation to take them to China for their unabashedly perilous mission.

Operation Oblivion was cancelled, however. By the time the men were ready to go, it was now August of 1945; Hiroshima had been bombed, and Japan was now days away from surrender.

The thirteen men went separate ways to all new stories - and indeed, this very reason was why I stopped myself from writing about Operation Oblivion the first time around as every individual has an amazing story to tell.

For one, John Ko Bong ended up in Manila where he facilitated the return of Japanese prisoners of war - thousands of human skeletons making their way into their refugee camp.

For others, like four of the thirteen - Roy Chan, Norman Low, Louie King and James Shiu - their final work of the war would continue in Borneo or Burma (possibly both, my research hit a snag figuring this one out). Their missions involved raising a guerilla army of the local headhunters and taking over a POW camp in Kuching (Borneo), as well as seeking out the remaining Japanese troops in the jungles and convincing them to surrender and repatriate - just one of many stories of detached units unaware of the war's end. In any case, those four all received the Military Medal for bravery.

I simply do not have time or resources to tell every story involved. They all begin differently, they come together, and they all end differently. For some, an entire generation of brothers and sisters enlisted; for others, they just did what they felt was right.

My version of the story is incomplete. Still, I know how it ends: they came home alive, and like Bill Chong and Douglas Sam, they saw a nation change and begin to embrace them.

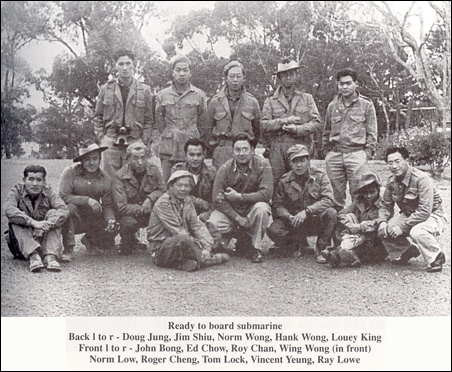

(The operatives of Oblivion - and yes, I know there are 14 people in the picture... I don't know who is extra.)

The story of and around Operation Oblivion is pretty amazing on its own and I could probably actually finish this year's Remembrance Day post on this note. But I'm already telling incomplete stories tonight... allow me to tell one more...