Today's write-up is irregular for me for a few reasons. One, much like yesterday's write-up about the Angels of Bataan, it focuses on American involvement in the wars. Second, it involves a story decently well known in certain circles including a few movies. The two go hand-in-hand: American war stories get told far more often over here than stories about Canadians at The Battle of Moreuil Wood or the Dutch Hongerwinter.

For myself, I never really heard about this particular story until watching bonus features on the Saving Private Ryan DVD and how amazed I felt watching an aircraft carrier loaded with 16 medium bombers. After a little research, I learned that an extremely inaccurate portrayal of this attack occurred in the film Pearl Harbor - admittedly, a film I have never bothered to watch. It's a neat story, and one that I latched onto immediately.

This is the story of the Doolittle Raid, and the first of what would later be a great many bombs to fall upon the Japanese Home Islands.

December 7th, 1941. The Japanese attack Pearl Harbor and the United States enters the Second World War. The United States was far from set into high gear for wartime production and would not be for arguably another year or two, and the Japanese were running roughshod over China and southeast Asia. American morale was hurting.

President Roosevelt tired of that state of things, and wanted swift retaliation; he wanted bombs falling on Japan.

This would not be easy. Bombers are large airplanes that take up a lot of space and need a lot of running room to take off. At the same time, there was no friendly ground within bombing distance from which to launch. The United States found a break, however, when it was observed and determined that smaller twin-engine Army bombers could feasibly have just enough runway space on top of an aircraft carrier to take off. Once newly promoted Lieutenant Colonel James "Jimmy" Doolittle began planning an attack with this knowledge, they also determined the American B-25 Mitchell Bomber had the qualities needed for the mission.

America had the means to bomb the Japanese Home Islands.

The Army Air Force's 17th Bomb Group got the mission, its pool of bomber crews having the most experience with the relatively new B-25. The crews were diverted from their anti-submarine patrols in February transferred from Oregon to South Carolina to prepare and volunteer for an "extremely hazardous" mission against Japan.

Their bombers, meanwhile, were heavily modified in Minnesota to better fit the mission. They removed the belly turrets, installed blast plates and de-icing equipment, removed heavy radios and extra guns, and installed additional fuel tanks effectively doubling their flying range. Once modifications were complete and once the crews were prepped, both man and machine made their way to Florida in early March. There, they trained as far as they could to taking off from an aircraft carrier without actually taking off from an aircraft carrier.

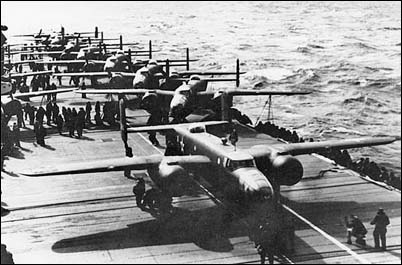

Though Doolittle originally planned for 24 B-25s to take part in the raid, only 16 aircraft were operational after further modifications and a couple training accidents. Still, the mission continued, and on April 1st, 1942, the USS Hornet was loaded with 16 B-25s and 80 airmen. The following day at 10:00am, the Hornet left the port of Alameda in California for the far east.

The Hornet joined Task Force 16 (which included the USS Enterprise) near Hawaii and together they sailed towards Japan. The Hornet's entire flight deck was covered with bombers with their tails hanging over the sides, and all her fighter planes were stowed below deck. The task force would be the Hornet's only defense should they be attack. Luckily, there was essentially no contact for the task force until they were deep into Japanese waters. Essentially, anyway.

On the morning of the bombing raid, April 18th, the task force was spotted by a Japanese picket boat which radioed the sighting. The task force wiped out the boat and captured five of the eleven surviving Japanese crew, but it was too late: the element of surprise was fast slipping away.

Doolittle made the order to launch the bombers immediately, ten hours earlier and 170 nautical miles away from their intended launch point.

Miraculously, all 16 B-25s launched (for the first time ever) safely from the USS Hornet over the course of an hour. Once airborne, the bombers flew low above the sea, single file, to avoid detection on their approach. After launch, it was a six hour flight to the Home Islands...

It needs to be stated again just how vulnerable these bombers were. To facilitate the distance they needed to travel, the bombers were stripped down to bare necessities. Each had a top machine-gun turret and a chin turret, with only a fake mock-up rear turret to discourage attackers. If they were seriously attacked, it would prove extremely difficult for the bombers to defend themselves. It had to be a long six hours for the bomber crews.

Well, they made it. All 16 bombers made it to Japan, and diverted to their respective military and industrial targets over Tokyo, Yokohama, Yokosuka, Nagoya, Kobe, and Osaka. En route, the bombers did encounter some resistance from antiaircraft fire and Japanese fighter planes, but none of the 16 were shot down.

That afternoon, all but one of the bombers dropped their payloads on the Japanese Home Islands.

Their mission done, the B-25 crews now had to face the one inevitability that they all knew before they accepted the mission: they weren't going to come home. They didn't have enough fuel to return to friendly airspace, and they definitely weren't going to land 16 medium-sized bombers back onto an aircraft carrier (even if they still had enough fuel to return to the Hornet).

The original plan was that they would land the bombers in Russia and turn them over to the Soviets as Lend-Lease. Unfortunately, the Americans were never able to make an agreement with the Soviets, and as such most of the bombers headed to China where they could be refueled and set for use again. One bomber was too low on fuel for the trip, though, and landed in the nearer Russia, where the bomber was confiscated and the crew interned by the Soviets for over a year - the crew escaped in 1943 through Iran, of all places.

The other 15 bombers found their own difficulties getting to China. Poor weather, approaching nightfall and dwindling fuel reserves meant none of the bombers would be able to reach their intended airbases in China, and after thirteen hours since leaving the Hornet, all the remaining bomber crews either bailed out over eastern China (or over the sea) or crashed along the Chinese coast.

Doolittle himself parachuted safely down with his crew and later met up with Chinese soldiers and civilians. Most of the other downed crews also found help from the local population and 13 of the 15 downed crews (save one member who was killed during his bailout over China) were able to escape China and avoid Japanese capture.

The other two crews were not so lucky. Of the crews unaccounted, two men drowned in the sea upon bailing from their plane. A further eight were captured and imprisoned in Shanghai. After months of starvation and disease, three of the airmen were executed by firing squad after a mock trial in August. The remaining five were transferred the next year to a camp in Nanjing where another airmen died from his conditions. The surviving raiders would spend the rest of the war incarcerated until being freed by American troops in August of 1945.

In the end, the bombs destroyed very little and damaged the Japanese war machine superficially, while 15 bombers were destroyed and another essentially stolen by the Russians. Seven airmen lost their lives, four of them under horrid conditions. In the eastern Chinese regions of Zhejiang and Jiangxi, the Japanese effected a campaign to root out the hiding Americans and force the local Chinese civilians to give them up. An estimated 250,000 Chinese civilians were massacred in this retaliation.

Doolittle himself saw the raid as a complete failure. Loss of aircraft for minimal damage.

He would later learn how wrong he truly was...

As I had started, Japan had been running practically uncontested for several years already, expanding its empire and laying waste to millions. With a single raid, they were reminded that they weren't invulnerable. Watching American land-based bombers drop payloads onto Japanese soil shocked the island nation. They were casting doubt on their military leaders, and more importantly, they were completely confused as to exactly where the "land-based" bombers had come from. Though not appreciated until years later, concern for defending the Home Islands led to a withdrawal of a massive Japanese carrier fleet back to Japanese waters. The fleet had originally wreaked havoc on British ships in the Indian Ocean, and was making its way southward towards Australia before the Doolittle Raid. Japanese misunderstanding of the bombers' origins also encouraged them to attack Midway Island - the site of the first critical naval loss suffered by the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Back in the United States, morale skyrocketed. Not only was there a visible counter to the insult at Pearl Harbor, there was proof that Japan could be struck, and that they could be defeated. The waking giant had steeled its resolve.

After the raid, 28 crewmen remained in the Chinese theater for a year or more. Nineteen others, after returning to the United States, flew over North Africa. Another nine ended up flying sorties over Europe. The raid was only the beginning of a very long war for all involved.

Still, for their actions during the raid, the raiders were justly rewarded. Doolittle was promoted to Brigadier General and awarded the Medal of Honor. Two others received Silver Stars for their work in helping wounded comrades evade Japanese capture. All 80 raiders, living and dead, were awarded Distinguished Flying Crosses by their own nation as well as decorations from the Chinese government.

(The deck of the USS Hornet, covered with Doolittle's B-25s)

When you learn about actions like these, they really do remind you just how much things affect each other. At times, it can truly feel like what you do doesn't or didn't mean anything. Much like Doolittle's Raid, sometimes that just isn't the case at all.

Take today, for instance. You may think stopping for a minute or two to just think about the sacrifices made in the name of peace and freedom, of the millions of lives lost . . . it may feel like they don't really mean a lot.

But they do.

Always remember that.